At the Feb. 15 Board of Governors workshop, we reviewed financial planning scenarios that run out to 2030. Extrapolating from university CPPs and grounded in our System Redesign priorities, the forecasting exercise can inform Board decisions and its ongoing evaluation of System progress.

As background for that conversation, I am circulating to you this summary of trends that will shape U.S. higher education in the years ahead, with links for those wanting to know more. To be clear, these trends will create headwinds. They also will create opportunities that smart institutions will take advantage of – strengthening themselves as engines of economic development and social mobility, expanding student and employee headcount, and securing themselves financially.

State System universities are well positioned in this regard, although our work will require purposeful attention to the continued evolution of educational and business models.

Let’s dig in.

SUMMARY OF U.S. HIGHER ED TRENDS:

TREND 1: Enrollment in U.S. higher education will remain under pressure.

University and college enrollments will continue to shrink in most regions, with less selective public four-year universities (like System universities) and community colleges losing the most ground. The high school leaving population – our traditional market – will contract by about 10% in Pennsylvania in the 10 years after 2026. The growing skepticism about the value of higher education won’t help. It reflects a variety of concerns having to do with the cost of a postsecondary education and the return available from that investment, notably in graduates’ earning power. There is a political dimension to the phenomenon – some are more skeptical than others – but the trend lines are nonetheless unfavorable for all, irrespective of political identity.

Also adding pressure on college enrollments are:

- Employers who look beyond degrees as a measure of employee competency (this “emerging degree reset” is gaining ground and sweeping up large employers including Apple, Google, and IBM, and the states of Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Utah).

- Aggressive competition from public universities and systems that give in-state tuition to residents of contiguous states (a means by which SUNY doubled its applications for Fall 2023).

TREND 2: Institutions will compete hard along a few axes to counter declining enrollments.

1. Preserving/growing their share of a shrinking traditional market

A key to surviving the enrollment bust involves retaining and graduating more of the students that an institution enrolls. The greatest opportunities may exist for less selective universities, provided they can evolve and adopt pedagogical and student support practices that demonstrably engage students most effectively. PASSHE universities are ploughing this field hard and making progress thanks to a raft of innovations in both classroom and non-classroom settings, and thanks to the creativity and commitment of our faculty and staff. That work needs to continue, broaden, and ultimately accelerate. It may benefit significantly from formal employee professional development. A recent study of faculty professional development offered by the Association of College and University Educators found solid evidence of its positive impacts measured in terms of student course completion rates and learning outcomes, and a five-fold return on training investment.

2. Expanding degree completion programs for adult students with some college and no degree

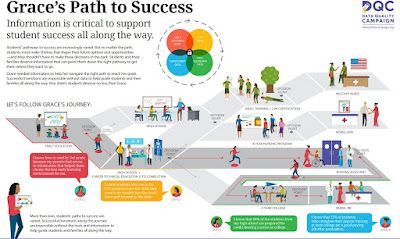

In Pennsylvania, a million people over the age of 25 have some college but no degree. (There are 35-40 million nationwide.) Not all want to complete their degree, but some do – enough to spawn aggressive competition in degree-completion programs. Programs that award credit for prior learning and make educational, student support, and business and administrative functions available outside normal business hours are positioned well, along with those that offer remote learning options and adult-tailored supports (e.g., child care, as well as financial aid, career, academic, and other kinds of advising).

Recruiting, enrolling, and educating adults is something we do – adults account for about 12% of our student body, compared to 37% of the student body nationally. Scale requires evolution of our business, administrative, educational, and support functions in ways that advantage adult students and compete effectively with other institutions seeking to serve them.

In Pennsylvania, a million people over the age of 25 have some college but no degree. (There are 35-40 million nationwide.) Not all want to complete their degree, but some do – enough to spawn aggressive competition in degree-completion programs. Programs that award credit for prior learning and make educational, student support, and business and administrative functions available outside normal business hours are positioned well, along with those that offer remote learning options and adult-tailored supports (e.g., child care, as well as financial aid, career, academic, and other kinds of advising).

Recruiting, enrolling, and educating adults is something we do – adults account for about 12% of our student body, compared to 37% of the student body nationally. Scale requires evolution of our business, administrative, educational, and support functions in ways that advantage adult students and compete effectively with other institutions seeking to serve them.

As we will hear from two leading experts during our workshop on Feb. 15, the credentialing world is complicated. There are over a million unique credentials awarded by academic and non-academic providers. About a third of them are degrees (associate, bachelor’s, etc.) and certificates awarded by the nation’s 11,000 postsecondary providers – 4,300 of them eligible for Federal Title IV funding. The rest are available as certificates, badges, licenses, and other credentials from more than 50,000 providers.

Further, by any measure, the number of non-degree credentials (NDCs) produced each year now dwarfs the number of degrees produced. Driving growth are the cost of college degrees and skepticism about their value, employer willingness to use other measures of employee competence, and accelerating change in the world of work, which requires that earners constantly re-skill and up-skill in order to remain relevant in the job market. While media attention focuses more on non-traditional providers like LinkedIn and Coursera, universities and colleges are moving into this arena by offering NDCs to:

Degree-seeking students for competencies earned by completing credit-bearing courses (e.g., Credly badges awarded by ESU).

Non-degree students who are seeking specific industry-recognized skills, like those available at IUP’s Academy of Culinary Arts or in certificates available from Mansfield’s Public Safety Training Institute, for example.

Employees at partner organizations to which universities provide bespoke training. PASSHE universities offer more than 300 NDCs, but not at scale. Scaling up requires:

- A credential registry – that is, a catalog of all the credentials we offer, degrees and non- degrees alike, and a strategy for expanding their number in a focused way, including by identifying credentials that can be made available to students by completing existing courses.

- Marketing and student recruitment campaigns that leverage a growing catalog of NDCs and student-facing systems appropriate for non-degree students.

- More (and more intensive) employer partnerships that build demand for NDCs, including through internships and tuition-assistance programs.

- Expansion in credits made available for prior learning, including for NDCs.

- A business model that supports competitive pricing in the non-degree market.

4. Emphasizing credentialing pathways over degrees

Lifelong learning has become an imperative. It is no longer reasonable to assume that someone can amass in a few years the full range of skills and competencies they need to participate effectively in the 21st-century economy. And yet, that assumption is what higher education degree structures and business models are largely built upon (see Carey, The End of College and Craig, A New U).

Credentialing pathways offer a solution. Pursuing them, working learners move back and forth between higher education and the workforce, acquiring credentials as they go and “stacking” them so that some of the credits earned count toward the award of the next credential(s).

Nursing pathways (depicted below) are commonplace, defined and largely standardized by professional accreditors operating in tandem with employers. Such pathways are being built for other industries by educators and employers working in partnership to define competencies required for critical industry roles, translating those competencies into credentials, and then offering credentials to students in ways that enable students to “stack” them just as nurses do as they build their careers.

PASSHE universities have experience in this regard. They partner, for example, in #Prepared4PA – an initiative that pairs education providers with employers in six major Pennsylvania industries to do the credential design and development work referenced above. Scale will build on work supporting adult degree-completion programs and the delivery of non- degree credentials. And it will require that State System universities use the aforementioned credential registry to show existing and prospective students how the degree and non-degree credentials that are available interact with one another and with those available from other providers to create career pathways.

|

5. Engaging even more aggressively with technology

A dozen years ago, technology was seen as a means of reaching into new markets. Today, it also promises improved student outcomes.

A dozen years ago, technology was seen as a means of reaching into new markets. Today, it also promises improved student outcomes.

- Technology use in growing new markets is evident at:

- “Mega” universities that now enroll over 120,000 students annually (e.g., Southern New Hampshire, Grand Canyon, Liberty, Western Governors, and Arizona State universities); and

- Universities and systems trying to break (late) into a crowded market for fully online degrees by acquiring for-profit providers (e.g., Purdue’s acquiring Kaplan), investing significantly in home-grown capability (e.g., UNC System’s $92M investment) or in partnership with online program managers that support fully online programs on the basis of revenue-sharing and/or fee-for-service models.

- Technology use improving student outcomes is apparent in growth in the “adaptive courseware” market (think super-smart digital textbooks that adapt themselves to each user’s learning needs) and applications of machine learning and artificial intelligence (think “smart” technologies that mine vast wells of data and use other means to guide supports offered to students to assist in their educational journey). The vigorous debate about uses in higher education of ChatGPT (think super intelligent AI-driven authoring agent – yup, it will write your essays) is particularly illuminating in this regard.

PASSHE universities are fully used to technology adoption and adaptation. We’ve been doing it for decades. And we’ve learned that success requires employee professional development – something that can be in short supply for institutions experiencing enrollment declines and resulting financial pressures.

THE ROAD AHEAD

I have every confidence that PASSHE universities can translate headwinds into opportunity in these and other ways. I also believe we won’t be successful unless we are purposeful and aligned in our approach. So, in the interest of our expanding that alignment (and transparency), I offer four caveats:

1. We are not alone in considering the opportunities presented above. That’s a comfort. Our redesign priorities are now within the mainstream of contemporary higher education. It is also concerning. Competitors to whom we have lost market share since 2010 are not standing still.

2. We can’t assume our talented, mission-driven faculty and staff will simply figure out how to find, enroll, and graduate adult students, build and help students of all backgrounds navigate complicated lifelong learning pathways, and/or deploy the latest generation of technology to greatest effect. Adequately resourced investment in people, systems, processes, and practices will be critical.

3. We need to strike a balance in our portfolio of offerings – for example, between on- ground and online learning, degree and non-degree pathways, adult and traditional students. Balance builds resilience against further, future changes in one or another parts of the higher education marketplace. It also allows us to explore innovations deliberately, developing the necessary competencies over time with constant attention to indicators that help us determine where we might need to course correct.

4. We will need to attend to budgetary realities, even where we don’t like them. Two aspects here:

a. State support: I understand arguments that suggest we are letting our owners, the state, off the hook by living within our means and making the trade-offs in class size or program scope, for example. Better, it is said, to hold fast and demand more, and to heap the evidentiary basis of our demands on our owners, who are third worst in the nation in their support of a public higher education that delivers good and tangible results. While I agree with the need for aggressive and analytically driven advocacy, I struggle with the idea of digging in and waiting for the investment we sorely need. Our operating margins are thin at best, which means we don’t have a lot of time to wait. More worryingly, the students and employers and communities in our midst need our help now.

b. Use of existing resources: They will be the principle means of support for new endeavors. Here’s why: For nearly 60 years after World War II, funding flows into U.S. higher education allowed it to evolve additively – building new without dialing back much on existing. Even when per-student state funding came under pressure in the 1990s, overall revenue followed enrollments, both of which grew. All that changed when enrollments began to decline (for PASSHE, a dozen or so years ago). While there will always be opportunity to support innovation with new dollars, more reliable and lasting investment will come through the choices we make about how existing dollars are used – what scope of operations, programmatically and otherwise, we maintain while investing in the new.

The emphasis on choice requires a fundamental shift in mindset that operates at all levels – one that is neither comfortable nor easy to make. At the same time, the cost of not making this shift is real. It entails tying us to models of and markets for higher education that are declining in size and public trust and enthusiasm. As ever, choices matter, and thankfully, right now the choices are ours to make.

No comments:

Post a Comment